Excerpts from “It Doesnʼt Take All That Much To Create A Universe

Danieru wrote: It doesnʼt take all that much to create a universe. Resources on a cosmic scale are not required. It might even be possible for someone in a not terribly advanced civilization to cook up a new universe in a laboratory. Which leads to an arresting thought: Could that be how our universe came into being?

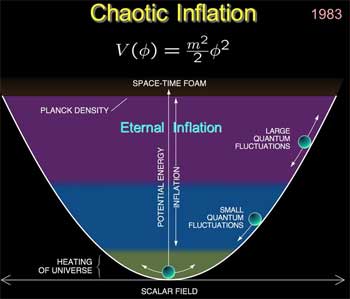

“When I invented chaotic inflation theory, I found that the only thing you needed to get a universe like ours started is a hundred-thousandth of a gram of matter,” Linde told me in his Russian-accented English when I reached him by phone at Stanford. “Thatʼs enough to create a small chunk of vacuum that blows up into the billions and billions of galaxies we see around us. It looks like cheating, but thatʼs how the inflation theory works—all the matter in the universe gets created from the negative energy of the gravitational field. So, whatʼs to stop us from creating a universe in a lab? We would be like gods!”

[…]

“You might take this all as a joke,” he said, “but perhaps it is not entirely absurd. It may be the explanation for why the world we live in is so weird. On the evidence, our universe was created not by a divine being, but by a physicist hacker.”

Lindeʼs theory gives scientific muscle to the notion of a universe created by an intelligent being. It might be congenial to Gnostics, who believe that the material world was fashioned not by a benevolent supreme being but by an evil demiurge. More orthodox believers, on the other hand, will seek refuge in the question, “But who created the physicist hacker?” Letʼs hope itʼs not hackers all the way up. - The Big Lab Experiment

The idea that universes somehow ‘evolve’ stems naturally from this.

A universe capable of maintaining life expands, cools and grapples with its own entropic forces

The life evolving within that universe has enough time and resilience to achieve a level of intelligence equal or greater to our own

That life becomes aware of other universes (perhaps of an infinite variety) residing in higher dimensions of reality

The desire to join in the multiversal fun grows beyond all reason…

At this point a baby universe is made in a lab, or by whatever means, and branches off. The baby universe contains enough of the ‘genetic’ information of the parent universe for it to be deemed a relative.

Perhaps intelligent life tweaks the contributing factors in its baby universe, effectively altering its composition to suit their self-reflective needs. In this way universes would evolve, intelligent life being their means of procreation. Perhaps all reality is this way. Perhaps our universe is still in its infancy, a larger, protective parent exerting its gravitational force across the many planes of the multiverse.

Perhaps…

Dr. Orphusi writes:

I like this hypothesis.Itʼs not unlikely that our universe has already spawned a baby universe, fostered to life by an intelligent species in some far off galaxy that had a head-start on us. I wonder what sort of universe they have created?

But hereʼs a question…

We speak of spawning baby ‘universes’, but perhaps we can only really create galaxies/worlds within a single sub-universe, or more precisely, a single reality, the one which is created by our hands in our reality. How can I explain this…?

When and if we create a baby universe of our own, I think that it could be a part of the same sub-universe as the one created by the hypothetical ‘other’ intelligent species in some far away galaxy.

So their baby universe is really just a part of the sub-reality in which our own baby universe is a part…

And it keeps cascading downwards, one reality at a time…

Although itʼs possible that because the nature of the consciousness of each species (human, extraterrestrial) is different (is it, I wonder?), then the universes we create will naturally be separately realized.

Either way, itʼs an intriguing question. However I believe our universe is beyond its infancy… we canʼt guess at the extraterrestrial chances of self-reflection, but when man first perceived the world and himself, it was then that the universe changed… like a blind baby recently emerged from its motherʼs womb, opening its eyes for the first time. But more analogously, I think our universe is akin to a child that can begin to remember, that can speak and make sense of its thoughts. Its growing up as we grow up.

Ishmael writes:

Iʼd be interested to know how Lindeʼs theory comes to terms with the first law of thermodynamics—while itʼs probably pointless for a non-physicist such as myself to wonder about such things, the technical details of a pocket universe would seem to offer some clue as to their nature.For instance, assuming that they do obey the laws of thermodynamics—that no energy is created in the creation of a new universe, and that they simply subsist on the energy of the tiny chunk of matter that they are created from in the parent universe, does that mean that their energy levels are simply “scaled down” from ours? And what of the sizes of fundamental particles? Are their protons small than our protons? But that would seem to contradict one of the most interesting passages in the article, namely that such constants are variable:

But then Linde thought of another channel of communication between creator and creation—the only one possible, as far as he could tell. The creator, by manipulating the cosmic seed in the right way, has the power to ordain certain physical parameters of the universe he ushers into being. So says the theory. He can determine, for example, what the numerical ratio of the electronʼs mass to the protonʼs will be. Such ratios, called constants of nature, look like arbitrary numbers to us: There is no obvious reason they should take one value rather than another. (Why, for instance, is the strength of gravity in our universe determined by a number with the digits 6673?) But the creator, by fixing certain values for these dozens of constants, could write a subtle message into the very structure of the universe. And, as Linde hastened to point out, such a message would be legible only to physicists.

(Insert here the obligatory reference to Contact. Note also the relationship between the present topic and Stephen Baxterʼs excellent Manifold trilogy, in which (spoilers) the first book resolves the Fermi Paradox by positing multiple universes, some sterile, some life-bearing, and one (ours) just lucky enough to eke out one sentient civilization—a fluke—but a fluke that enables the protagonist to have a hand in the creation of another, more promising universe.)

But then, perhaps pocket universes do not obey the first law—at least in the sense that we know it. Let “Existence” denote the sum of all universes and pocket universes. Perhaps the total amount of energy in Existence is constant, but fluid throughout its constituent universes. That is, energy does exit and enter any given universe* while coursing through the totality. This idea could gel in several ways with Dr. Orphusiʼs ideas of multiple realities; i.e., energy is constant within a reality, but does not travel between them. This would still mean, though, that there is a “direction” to the flow of energy throughout Existence. That older universes die while young ones are born, the energy leaving them and pouring into the new creations, and actually, unless there is some bracketing factor such as Orphusi suggests, the multiplicative proliferation of new universes would demand more energy than Existence is able to provide, and none of the pocket universes would have the energy to develop into universes at all, much less life-bearing ones. Essentially, itʼs heat death all over again. Or have I missed something essential?

*Note the presence of undeveloped and probably incoherent ideas here about dark energy and the weakness of gravity. Prompted in part by Danieruʼs poetic conclusion “across the many planes of the multiverse,” and in part by some Scientific American article I read long ago about gravityʼs strange weakness compared to the other fundamental forces, perhaps accountable by its operation through many universes.

There is also the question, returning briefly to my inquiries about scale, of instability below the Planck length. If, as the article says, a pocket universe would not expand outward, consuming its parent, but would curl inward until it is imperceptibly tiny, at what point do new universes become impossible because of the random energy fluctuations that permeate space? Or does it possess its own space? I hope someone here knows more about physics than I do…

Annnd, winding up now, for now, let us not forget virtual universes, a subject near and dear to my heart. What are the possibilities, if any, for sentient life (or simply life, if you see a difference…) to develop in a virtual universe? Such a universe would necessarily be limited by the physical constraints of its parent universe (its largest possible scope being the parent universe itself, if you buy the idea of our universe as a giant computer), but as we have seen on the Exponentially Small Planet Earth, one hardly need simulate a universe to obtain life. It would seem not to, in fact, take a village to raise a child, if by “village” you mean galaxy or interstellar community, and if by “child” you mean us. Many more thoughts here, but methinks I ought best stop typing.

Danieru writes:

Many thoughts Iʼll dare to dwell on… Lovely replies…Gravity is the only force thought to permeate the dimensional barriers. As Ishmael alludes to, gravity is undoubtedly the weakest force we have knowledge of (a magnet the size of a pea can overcome the gravity of the entire planet Earth when used to pick up a paper clip). Yet gravity is the true craftsman of reality, carving pathways which galaxies, planets and people can roam; building pockets of entropically divergent matter where life finds time to evolve.

I like the idea that the beginning of the universe, i.e. the big bang, is a black hole in reverse (a white hole). Michio Kaku manages this image better than I:

If the singularity at the center of a black hole lies in the future, representing a final state, the singularity of a white hole lies in the past, as a beginning, as in the big bang. So if our universe is a white hole, the big question is: is there a black hole universe on the other side of the big bang?

So, youʼve spawned your baby universe in your massively expensive laboratory, but you are worried it will off-set the balance of nature (the first law of thermodynamics)? What if that first law could be balanced both in and outside the system we understand as this universe?The baby universe is on the opposite side of a black hole for all intents and purposes. Perhaps it continues to feed off the energy of its parent, or maybe its black hole status is short lived; the bubble segmenting off from our reality and floating off into the multiverse alone. Either way, because energy is mass (Einstein says hello) and because all matter exerts gravity across the multidimensional planes, the baby universe and the parent universe would balance each other out. The baby universe might be obtaining energy from this reality, but in turn its gravitational presence acts as a stabilizing force, effectively keeping equilibrium in check across the planes.

Now, my physics here is shaky, granted, but you get my over all point: nothing, not even a universe, is completely self contained. Beyond the temporally formalized singularity we call ‘the beginning of time’ there is surely a primeval source of energy, and beyond that countless infinities more besides. Perhaps, if you take the perdurantist view on temporality, time itself should not be factored into the model we have drawn. In this way energy could enter the system at any point along the time axis, just as long as the first law of thermodynamics kept balance in balance in balance in balance throughout the entire system*….

Gets you thinking though for sure. Do all black holes lead to baby universes?

*The entire system in the perdurantistʼs view encompasses all the universe from the ‘beginning’ to the ‘end’ of time. Imagine time as a 4th dimension, effectively turning the universe into one fat 4 dimensional block of cheese. Slice through the cheese at the 14.3 billion year mark and youʼll find me typing this, you reading this or an empty forum in want of a conversation. Only by looking at the whole of the cheese can you be said to be perceiving the universe…

Author writes: I canʼt quite get my head around the fact that Iʼm looking at the inside of a sphere, which has a radius of the distance traveled by the light of the big bang; when Iʼm seeing the outside of the smallest sphere imaginable, seeing as how I look back to the beginning of time in all directions.

No comments:

Post a Comment